Previous posts on this parable this week are here and another here.

The parable talks about “gold coins,” but the original Greek text uses the term “talent,” an old word which has come to mean “a natural ability or endowment to learn or do anything or perhaps it means grace as RJ from When Love Comes To Town explains it well here ?

The claims that the ultra-rich 1% make for themselves – that they are possessed of unique intelligence or creativity or drive – are examples of the self-attribution fallacy.

This means crediting yourself with outcomes for which you weren't responsible. Many of those who are rich today got there because they were able to capture certain jobs.

This capture owes less to talent and intelligence than to a combination of the ruthless exploitation of others and accidents of birth, as such jobs are taken disproportionately by people born in certain places and into certain classes."

So there are a pile of questions on how money is made and ethical issues on the equitable distribution of that money to the most needy.

Carla Work's interpretation below suggests the parable is about accountability and the idea that God has invested heavily in us and so our lives should produce a return worthy of that trust ...

In this article Curtis Webster says :

From the very moment that Jesus began His earthly ministry, following Him has entailed significant risk. The Twelve Disciples lived in fear for their lives. The Apostle Paul and his followers were imprisoned, tortured, and, in many cases, executed for their efforts as they spread the Good News of the Gospel all over the face of what was then the known world.

"Okay, may I just say it? I find myself liking the third servant more than the first two.

The entrepreneurial servants of the parable do precisely as expected: they enlarge the master’s fortune in his absence, they follow his plan without question, they perform as he has compelled them to do. The third fellow, however, calls things as he sees them. He knows his master is corrupt, and, with a curious mix of courage and fear, he says so to his face. And thereby reaps the master’s wrath.

So I find myself wondering, why is it that we most often read this passage as a judgment against the third servant and not against the man who has perpetuated an unjust system?

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

Do we really think that the harsh and reportedly corrupt master of this parable represents God, who, after a period of absence, comes back prepared to throw out those who have not performed as expected?

Do I really want to be like the first two servants, willing to participate in and perpetuate injustice?

Much like the wise bridesmaids, the two multi-talented men serve as the foil for the one who proves inept and unprepared.

One could say they are the suck-ups who provide a contrast to the screwup.

We might wonder at a parable that presents a narrative ecosystem in which the only available choices seem to lie either in perpetuating the master’s corrupt business plan or hiding his loot in the ground.

But we might wonder, too, at the servant who perceives these as the only options.

He is savvy enough to recognize the system that surrounds him, and, presumably, he has participated in it up to this point.

He finally demonstrates a measure of bravery that enables him to, as the phrase goes, speak truth to power. But like the foolish bridesmaids, he possesses a streak of passivity that, within the landscape of the parable, proves his undoing.

Perhaps this is what makes each of them—the hapless bridesmaids, the single-talent servant—foolish: ultimately, they prove unwilling to take responsibility for pushing toward another option, looking for another choice.

They have forgotten the God who startles with stunning abundance in the midst of the starkest lack.

The servant who buried his sole talent reminds me that when we cannot imagine other possibilities, we tend to hoard what we have, clinging to what is comfortable or at least familiar.

And not only to hoard, but to hide.

In the absence of eyes to see the wealth that God reveals in the wilderness, we secret away what small measure we have, thinking it will be enough to sustain us, and hoping it will protect us.

It’s difficult, however, to draw sustenance from secrets, and it’s hard even for God to bless and multiply that which remains hidden.

Darkness has its uses, and its gifts: growth requires gestation, a season of deep shadow, the absence of light for a length of time.

I take this parable seriously as a profound call to unhide ourselves, to resist accepting the obvious options, to stretch ourselves toward the fullness for which God created us. I recognize how this story, along with the parable of the bridesmaids, warns of the pain that comes from our passivity.

Yet I also read this parable in the light of the stories of the God who does miracles with what is most basic and elemental: oil, water, wine, bread, our very selves. This is the stuff in and through which God brings transformation, and the means by which God sustains the world.

As the season of Advent approaches, with its rich play of light and dark, what might God desire to reveal and to transform in my own life?

In these lingering days of Ordinary Time, may God stir our imagination, sharpen our vision, and give us courage to unhide what God desires us to offer."

This is a fine and original reflection from Peter at I Am Listening Blog where he gets at an understanding of the parable from a group point of view....Peter is a Methodist but a lot of what he says is relevant to many Christian churches

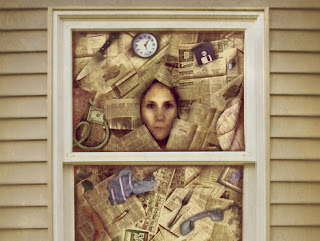

Image - Buried heart by Brandon Alterman

To laugh is to risk appearing the fool,

Scripture Readings and various reflections are here.

Time is running out for me to polish off the final reflections on the parable of the talents. Suffice to say that there are many diverse viewpoints on it .The parable talks about “gold coins,” but the original Greek text uses the term “talent,” an old word which has come to mean “a natural ability or endowment to learn or do anything or perhaps it means grace as RJ from When Love Comes To Town explains it well here ?

Actually I hardly tweet at all but I do blog a lot ...

"Yes, and it's Blah blah blah most of the time," I hear God say....

So here are just a few selections of some of my favourite unearthed diggings from my searches this week which tries to make sense of it all.

When I was thinking about how the other people in the parable actually made their money I came across this fine article from The Guardian which says :

"If wealth was the inevitable result of hard work and enterprise, every woman in Africa would be a millionaire. The claims that the ultra-rich 1% make for themselves – that they are possessed of unique intelligence or creativity or drive – are examples of the self-attribution fallacy.

This means crediting yourself with outcomes for which you weren't responsible. Many of those who are rich today got there because they were able to capture certain jobs.

This capture owes less to talent and intelligence than to a combination of the ruthless exploitation of others and accidents of birth, as such jobs are taken disproportionately by people born in certain places and into certain classes."

So there are a pile of questions on how money is made and ethical issues on the equitable distribution of that money to the most needy.

Carla Work's interpretation below suggests the parable is about accountability and the idea that God has invested heavily in us and so our lives should produce a return worthy of that trust ...

"The parable of the talents is among the most abused texts in the New Testament. Contrary to what might be modeled by some best-selling televangelists, the parable does not justify a gospel of economic prosperity. Instead, it challenges believers to emulate their Master by using all that God has given them for the sake of the kingdom.” This is a parable about how we wait on the Lord. .............

There is nothing passive about waiting on the Lord. We are called to actively steward the abundance that God has given to us. It is waiting with responsibility for His earth and accountability to Him when He comes back."

In this article Curtis Webster says :

"The Parable of the Talents could be a tract on economic theory, but it is also important testimony to the reality of our mission as Christians, both individually and collectively.

The Parable of the Talents says that there is simply no such thing as a faithful discipleship that is free of risk.

Christianity is a risky business, not for the faint of heart. Burying the talent in the ground because we fear losing it is not a strategy likely to please God.

Good stewardship is all about the management of the gifts that God has given us not for ourselves but for others. When we choose the safest course, we are not managing God’s gifts. We are hoarding them.

Good stewardship is all about the management of the gifts that God has given us not for ourselves but for others. When we choose the safest course, we are not managing God’s gifts. We are hoarding them.

From the very moment that Jesus began His earthly ministry, following Him has entailed significant risk. The Twelve Disciples lived in fear for their lives. The Apostle Paul and his followers were imprisoned, tortured, and, in many cases, executed for their efforts as they spread the Good News of the Gospel all over the face of what was then the known world.

By definition, Christianity is counter-cultural, not counter-cultural in a nihilistic let’s tear- everything-down sense, but counter-cultural in the sense that the Truth must be told and it must be told regardless of whether the culture at large will take offense.

The day we become afraid to speak the Truth, the day that we decide to play it safe, is the day when we forfeit the privilege of calling ourselves members of the body of Christ.

The day we become afraid to speak the Truth, the day that we decide to play it safe, is the day when we forfeit the privilege of calling ourselves members of the body of Christ.

This is the great irony of the Parable of the Talents..... there is no greater risk for the church than refusing to take any risk at all.

Intelligent risk-taking is part of our spiritual DNA, and our faith will atrophy over time if we ignore that reality.

Intelligent risk-taking is part of our spiritual DNA, and our faith will atrophy over time if we ignore that reality.

The early Christians risked their livelihoods, their social standing, and in many many

cases, their very lives for their faith. Today, we are rarely called upon to take that level of risk. I can’t imagine too many scenarios where we are likely to see stormtroopers showing up to arrest us all on a Sunday morning."

Jan Richardson's brilliant reflection on the parable is here

and this is an edited extract below :

"Okay, may I just say it? I find myself liking the third servant more than the first two.

The entrepreneurial servants of the parable do precisely as expected: they enlarge the master’s fortune in his absence, they follow his plan without question, they perform as he has compelled them to do. The third fellow, however, calls things as he sees them. He knows his master is corrupt, and, with a curious mix of courage and fear, he says so to his face. And thereby reaps the master’s wrath.

So I find myself wondering, why is it that we most often read this passage as a judgment against the third servant and not against the man who has perpetuated an unjust system?

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaDo we really think that the harsh and reportedly corrupt master of this parable represents God, who, after a period of absence, comes back prepared to throw out those who have not performed as expected?

Do I really want to be like the first two servants, willing to participate in and perpetuate injustice?

Much like the wise bridesmaids, the two multi-talented men serve as the foil for the one who proves inept and unprepared.

One could say they are the suck-ups who provide a contrast to the screwup.

We might wonder at a parable that presents a narrative ecosystem in which the only available choices seem to lie either in perpetuating the master’s corrupt business plan or hiding his loot in the ground.

But we might wonder, too, at the servant who perceives these as the only options.

He is savvy enough to recognize the system that surrounds him, and, presumably, he has participated in it up to this point.

He finally demonstrates a measure of bravery that enables him to, as the phrase goes, speak truth to power. But like the foolish bridesmaids, he possesses a streak of passivity that, within the landscape of the parable, proves his undoing.

Perhaps this is what makes each of them—the hapless bridesmaids, the single-talent servant—foolish: ultimately, they prove unwilling to take responsibility for pushing toward another option, looking for another choice.

They have forgotten the God who startles with stunning abundance in the midst of the starkest lack.

The servant who buried his sole talent reminds me that when we cannot imagine other possibilities, we tend to hoard what we have, clinging to what is comfortable or at least familiar.

And not only to hoard, but to hide.

In the absence of eyes to see the wealth that God reveals in the wilderness, we secret away what small measure we have, thinking it will be enough to sustain us, and hoping it will protect us.

It’s difficult, however, to draw sustenance from secrets, and it’s hard even for God to bless and multiply that which remains hidden.

Darkness has its uses, and its gifts: growth requires gestation, a season of deep shadow, the absence of light for a length of time.

But what we leave underground too long grows distorted and becomes decayed. As the third servant discovered, what we hide—our habits, our beliefs, our own selves—has a way of unburying itself.

I take this parable seriously as a profound call to unhide ourselves, to resist accepting the obvious options, to stretch ourselves toward the fullness for which God created us. I recognize how this story, along with the parable of the bridesmaids, warns of the pain that comes from our passivity.

Yet I also read this parable in the light of the stories of the God who does miracles with what is most basic and elemental: oil, water, wine, bread, our very selves. This is the stuff in and through which God brings transformation, and the means by which God sustains the world.

This week I find myself wondering, what do I hide, and why?

What parts of my created self have I sent underground?

Is there anything I’ve left too long in the dark?

Do I harbor any passivity that I need to invite God to turn into persistence?

As the season of Advent approaches, with its rich play of light and dark, what might God desire to reveal and to transform in my own life?

In these lingering days of Ordinary Time, may God stir our imagination, sharpen our vision, and give us courage to unhide what God desires us to offer."

An interesting take from Fr. Ron Rolheiser here on the dangers of false humility contained within the Parable of The Talents.. edited extract is below :

"Our gifts and talents are meant to help others, just as their gifts are meant to help us. To hide our light under a bushel basket serves no one - others, God, ourselves. That's precisely what Jesus warns us about in the parable of the talents. When God gives us a gift, God expects a certain return. To hide our talents, as the parable makes clear, is perilous to self and not very pleasing to the one who gave those gifts.

We already know this through experience, painful experience. When we self-depreciate in the name of humility, or for any other reason, we might fool people around us into thinking this is virtue, but we never fool ourselves.

We already know this through experience, painful experience. When we self-depreciate in the name of humility, or for any other reason, we might fool people around us into thinking this is virtue, but we never fool ourselves.

Whenever we hide our light, we generate a lot of rage, bitterness, and envy inside of ourselves. When we play small, however moral and noble the intent, another part of us begins to enrage. Why?

Because what we are doing fundamentally belies who we are. We are in the image of God, special, unique, fabulous, gorgeous, talented. When that part of us, that deep part, is bullied by a good moral idea gone awry (humility gone false) it does not acquiesce in calm and serenity. It enrages, becomes bitter, jealous, and frustrated at being forced to live a lie - even if it still says all the right things.

My own dad was not an educated man but, like many others whose souls have been forged in the desert of the prairies where a harsh beauty and a lonely isolation give everyone sufficient conscriptive time in the wilderness, he was a man of wisdom.

My own dad was not an educated man but, like many others whose souls have been forged in the desert of the prairies where a harsh beauty and a lonely isolation give everyone sufficient conscriptive time in the wilderness, he was a man of wisdom.

One of his quips ran this way: "Whenever you see someone who's always angry, take a look at that person. Because it's always someone who's very bright, with lots of talent ... it's just that he or she hasn't found a way of offering that in a way that people can receive it." A prairie perspective on Jesus' parable of the talents!

It's easy to misread this parable, thinking that the king arbitrarily punishes the servant who hid his talent. My dad's angle suggests something else, namely, that the punishment is not arbitrary but intrinsic, like a hangover to drunkenness.

It's easy to misread this parable, thinking that the king arbitrarily punishes the servant who hid his talent. My dad's angle suggests something else, namely, that the punishment is not arbitrary but intrinsic, like a hangover to drunkenness.

The "beatings" the parable talks about are what we do to ourselves whenever we hide our light under a bushel basket because one part of us then finds it intolerable to be in a situation wherein we are all talented-up with nowhere to go.

What is genuine humility? Real humility self-effaces, but does not self-depreciate; it is not assertive, but it does not slink away in unhealthy passivity; it is not showy and exhibitionist, but it does not hide its light either.

We are humble when we live in the face of the fact that we are both dependent and interdependent. We are not ipsum esse subsistens, self-sufficient Being, God, nor the centre of earth, nor intended to be that centre.

What is genuine humility? Real humility self-effaces, but does not self-depreciate; it is not assertive, but it does not slink away in unhealthy passivity; it is not showy and exhibitionist, but it does not hide its light either.

We are humble when we live in the face of the fact that we are both dependent and interdependent. We are not ipsum esse subsistens, self-sufficient Being, God, nor the centre of earth, nor intended to be that centre.

But each of us is a child of God, fabulous, unique, talented, asked to set forth our gifts on the table of life, as a gracious host might put food on the dinner table. Nelson Mandela is right, there is nothing enlightened, or God-serving, in false humility. Moreover, as Jesus' parable of the talents suggests, hiding one's talents doesn't exactly produce happiness either."

This is a fine and original reflection from Peter at I Am Listening Blog where he gets at an understanding of the parable from a group point of view....Peter is a Methodist but a lot of what he says is relevant to many Christian churches

"Now, if you have grown up in the church as I did, you will have heard any number of teachings on this parable, most of which will have been exhortations for you and I as individuals to use our God given talents as skilfully as we can and to achieve, achieve, achieve. After all that is the basis of the Protestant Work ethic!

There is just one problem with that approach. The individual was really not the key component of Biblical, Bronze Age culture. The group was.

Now if we consider that the church is the servant entrusted with the Divine Domain whilst Christ is visibly absent, it behoves the church to be expanding that Divine Domain’s resources through skillful engagement and even entrepreneurial action.

Yet when I consider the activities of many church communities I see them acting, not in the inclusive expansive and expanding spirit of the skilfull stewards in this parable, I see rather fear based, suspicious and conserve-reactive (Conservative) laagers. "

You can see the photos to match his thoughts here.

You can see the photos to match his thoughts here.

In his book, The Four Loves C.S. Lewis,addresses this fear of the servant who buried his talent as the person who also buries his love. He writes:

"To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will certainly be wrung and possible be broken. If you want to be sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one-not even to an animal (pet).

Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safely in the casket or the coffin of your selfishness. But, in that casket -safe, dark, motionless, airless, (your heart) will change.

It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, unredeemable.

The only place outside heaven, where you can be safe from all the dangers and perturbations of love is hell."

Image - Buried heart by Brandon Alterman

To laugh is to risk appearing the fool,

To weep is to risk being called sentimental.

To reach out to another is to risk involvement.

To expose feelings is to risk showing your true self.

To place your ideas and your dreams before the crowd

is to risk being called naive.

is to risk being called naive.

To love is to risk not being loved in return.

To live is to risk dying.

To hope is to risk despair,

To try is to risk failure.

But risks must be taken,

because the greatest risk in life is to risk nothing.

The person who risks nothing,

does nothing, has nothing, is nothing,

and becomes nothing.

does nothing, has nothing, is nothing,

and becomes nothing.

He/She may avoid suffering and sorrow,

but simply cannot learn, feel, change, grow or love.

but simply cannot learn, feel, change, grow or love.

Chained by certitude, he/she is a slave;

he/she has forfeited his/her freedom.

When the gospel says " Well done good and faithful servant; you have been trustworthy with a few things, now I will put you in charge of many things: come, enter into the joy of your master."

This from the deceased Catholic theologian Karl Rahner shows what that joy entails.

"The good in any prophecy is ultimately shown if it awakens us to the gravity of decision in courageous faith,

if it makes clear to us that the world is in a deplorable state (which we never like to admit),

if it steels our patience and fortifies our faith that God has already triumphed,

if it fills us with confidence in the one Lord of the still secret future,

if it brings us to prayer,

to conversion of heart,

and to faith that nothing shall separate us from the love of Christ. "

Karl Rahner, S.J.

1 comment:

I'm on my son's computer and I get to leave a comment! Yahoo!...so often I try to leave one on my home computer and it just won't work. I'm in deep denial regarding the state of my home computer:(

Anyway, as usual you have given me much food for thought in regards to one of my least favorite parables. I love that picture of the buried treasure with C.S. Lewis's quote. You may see that one again really soon:)

Thank you Phil for all the hard work you put into finding all of these photos and resources. They are much appreciated. Even if you don't hear from me that often:)

Post a Comment